Commentary and Criticism: Originally written in May, 2018

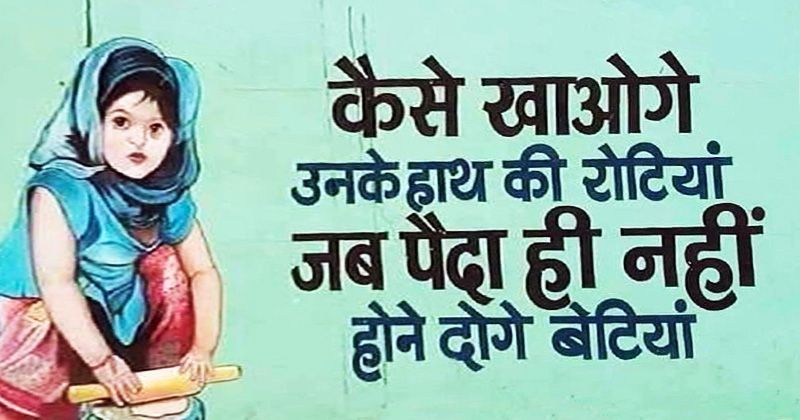

It is seldom that an advertisement adorning an unnamed wall of an unidentified city in India can set off a furious debate on digital platforms. However, that’s exactly what happened in the last couple of weeks in May 2018 as the hashtag #BetiBachaoRotiBanwao was introduced by the educated Indian diaspora weighing in on what a particular public service advertisement (PSA) meant. The digital debate gave a stage to a multifaceted issue of discrimination plaguing the country for years now. The point of contention – does the ad reinforce discriminative practices and stereotypes against women in the country or does the ad serve the purpose of saving the female child in India while conveying the message in a language that is appealing to majority of the population. It is important to consider both sides of the debate here and then come to a conclusion because of the mere fact that it concerns the 48.5% of the Indian population, who are fighting against the phallocentric, heteronormative, patriarchal society every day just to claim what is rightfully theirs – the right to survive (Census of India 2011).

The ad undoubtedly reaffirms the stereotypes and gender roles linked with women as homemakers, and reinforces the patriarchal society’s attempts at maintaining the status of the “weaker sex” for the females. It intends at advertising the joys of having a daughter in the family but at the same time equates those moments with the girl child’s role as a caregiver.

India has recently stood witness to gruesome crimes committed against women and children, and raised the question of what can possibly be a solution to the growing problem as even legal recourse has failed many (Chaudhary, Rai and Pandya 2018, Kiley 2018, Basu and Dastidar 2018). The fight for women’s rights has been an uphill battle in the country and involves but is not limited to concerns such as gender gap in education and employment, menstrual hygiene and nutrition, child marriage (Chaudhuri and Roy 2009, Fadnis 2017, Prasanna 2016, Srivastava 2018, UNICEF n.d.). At the root of all these problems is the misogynistic attitude, and one of its resultant practice is female feticide and infanticide that has led to a declining child sex ratio (CSR) in the country. Speculations about the chaotic future looms large over India as it may soon be a country left with no females (Denyer and Gowen 2018). Legal measures such as the Preconception and Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques Act 1994, which was redefined in 2003 to target the medical practices and professionals performing sex determination and sex selective abortion, have effectively failed due to non-implementation of the Act (A. Gupta 2017).

To address the alarming drop in the CSR, the Government of India launched the Beti Bachcao Beti Padhao (BBBP) initiative in 2015, which literally translates to “Save the Girl Child, Educate the Girl Child.” In 1901, the CSR (females per 1000 males) in the country was 972, but by the 2011 census the number stood at 918 (Census of India 2001, Beti Bachao Beti Padhao 2017). According to the World Health Organization, India has one of the most skewed sex ratios as there are 107 males born in the country for every 100 females (2018). The BBBP campaign’s officially sponsored advertisements are mostly positive and aim at sensitizing the areas with lower CSR points about the discrimination against the females. Despite the lack of an evident link, the controversial PSA has been associated with BBBP and led to the hashtag of #BetiBachaoRotiBanwao. It stands to reason that such a message aiming to save the girl child and put up on public display must be related to the national campaign. Therefore, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his governance has also not been spared any criticism – “Presenting to you, a unique combination of the Modi brand of ‘feminism’ with a heavy dosage of patriarchal mindset” (Sinha 2018).

There is no specific resource on where the graffiti physically stands and how its photograph became viral. However, the photograph of the PSA has been shared on various sites such as Twitter, Reddit, Facebook, Google Plus, and can be traced back as far as May 23, 2018 (Kamal 2018). Thereafter, on about May 25, 2018, the post went viral and public personalities like Karuna Nundy, Supreme Court of India advocate, author Rana Safvi, filmmaker Pratim D. Gupta also weighed in on the matter on their Twitter profiles. While Nundy called out the ad makers and asked them to make their own rotis (Nundy 2018), Safvi drew an analogy between the ads message of daughters needed for cooking to slavery, “Its [sic] in your interests to bring slaves into this world it seems … (Safvi 2018).” Gupta summarized that the ad encapsulates all that’s wrong with the Indian society in just one image (P. D. Gupta 2018).

A second group on social media however have taken up the stand that this advertisement aims at saving the female child and speaks in the language that majority of the Indian population are likely to understand. They have argued that the advertisement is not meant for the educated section of the society who are appreciative of a woman’s role beyond the boundaries of their homes, but rather aimed at those who see women solely as caregivers and homemakers. “As a feminist you have every right to be outraged, but I think we must respect the intentions behind it. It is rhyming, it is catchy and it gives the message of protecting the girl child” (Hound 2018) – said a public reply to the picture being shared by a Twitter user who disapproved of the PSA. Another user added, “Before outraging, think about the section of the society that it us [sic] aimed at. Certainly not the one that gives women equal opportunity. Hence the talk in the language they understand” (J 2018).

At the core, the message suggests that – do not commit female feticide. Give the girl child a chance! And in the same breath it also reminds the observer that there will be no females left to take care of the prized male child’s home. In essence, the message is self-defeating as it repurposes the need for fighting gender-based discrimination in the most regressive manner possible. It sends home a problematic message, despite the possible good intentions. The advertisement normalizes the role of females in the kitchen from a young age, even when their rightful place is in a classroom and at the playground. It reinforces the notion that irrespective of their talent, capabilities or the level of education, their destination eventually will be in the kitchen – a thought process that women rights advocates are working hard to overturn. The controversial advertisement and its criticism has also gained enormous attention from the mainstream media such as in India Today, ABP Live, Business Insider India, The Indian Express (Choudhury 2018, ABP 2018, Gill 2018, The Indian Express 2018).

The digital world has brought to the fore the problematic symbolism and message conveyed on behalf of an otherwise progressive campaign to save the girl child, and kicked off a conversation regarding the need for PSA in India that does not reinforce regressive ideas. At the same time, the social media conversations have also underscored the deep divide that exists within the country. Education or the lack of it, has been holding back the possibility of progressive thinking and growth in the country. Question is, when schemes such as Beti Padhao Beti Bachao and Dhan Laxmi that incentivize the birth of a girl child have failed to drive home the message that India needs daughters, can an ad that simply says you won’t even have a homemaker succeed? Alternatively, perhaps such public service advertisements campaigning to save girl child should promote the idea of what successful Indian women have achieved such as the likes of Chanda Kochhar, Kiran Mazumdar Shaw and Priyanka Chopra who have been internationally recognized among the list of 100 most powerful women in the world by the Forbes magazine (Forbes 2017). Public service advertisements are meant to serve a message that is in the interest of the public. But when such a message fails to serve almost half of the population then the ad makers and sponsors need to re-group and re-strategize.

References

ABP. 2018. “‘Beti Bachao Roti Banwao’ Campaign Gets Criticised.” ABP Live. May 29. http://www.abplive.in/videos/beti-bachao-roti-banwao-campaign-gets-criticised-704586.

Basu, Sharanya, and Sayantan Ghosh Dastidar. 2018. “Why do men rape? Understanding the determinants of rapes in India.” Third World Quarterly. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1460200.

Census of India. 2011. “Gender Composition, Chapter 5 of Provisional Population Totals.” Census of India. http://censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/data_files/mp/06Gender%20Composition.pdf.

—. 2001. “Sex Composition of the Population, Chapter 6 of Provisional Population Totals.” Vers. Web Edition. Census of India. http://censusindia.gov.in/Data_Products/Library/Provisional_Population_Total_link/PDF_Links/chapter6.pdf.

Chaudhary, Archana, Saritha Rai, and Dhwani Pandya. 2018. Sexual violence is holding back the rise of India. May 28. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-05-28/sexual-violence-is-holding-back-the-rise-of-india.

Chaudhuri, Kausik, and Susmita Roy. 2009. “Gender gap in educational attainment: Evidence from rural India.” Education Economics 17 (2): 215-238. doi:10.1080/09645290802472380.

Choudhury, Disha Roy. 2018. “Beti Bachao but only so she can make you roti?” India Today. May 28. https://www.indiatoday.in/lifestyle/what-s-hot/story/beti-bachao-but-only-so-she-can-make-you-roti-1243779-2018-05-28.

Denyer, Simon, and Annie Gowen. 2018. “Too many men.” The Washington Post. April 18. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/world/too-many-men/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.de472dfea28d.

Fadnis, Deepa. 2017. “Feminist activists protest tax on sanitary pads: attempts to normalize conversations about menstruation in India using hashtag activism.” Feminist Media Studies 17 (6): 1111-1114. doi:10.1080/14680777.2017.1380430.

Forbes. 2017. The world’s 100 most powerful women. https://www.forbes.com/power-women/list/#tab:overall_country:India.

Gill, Prabhjote. 2018. “Regressive spin on a government campaign is going viral in India.” Business Insider. May 29. https://www.businessinsider.in/regressive-spin-on-a-government-campaign-is-going-viral-in-india/articleshow/64368939.cms.

Gupta, Alka. 2017. “Female foeticide in India – Press Release.” Female foeticide in India – Press Release. UNICEF India. http://unicef.in/PressReleases/227/Female-foeticide-in-India.

Gupta, Pratim D. 2018. Twitter Post. May 27, 2018, 12:43 p.m. https://twitter.com/PratimDGupta/status/1000779451658002432.

Hound. 2018. Twitter Reply. May 28, 2018, 1:31 p.m. https://twitter.com/vabskrishna/status/1001154002107564032.

J, Ankur. 2018. Twitter Reply. May 28, 2018, 2:25 p.m. https://twitter.com/monsternaath/status/1001167594303320064.

Kamal, Sujata Amitabh. 2018. Twitter Post. May 23, 2018, 12:19 a.m. https://twitter.com/Dippi1122/status/999142866650783744.

Kiley, Sam. 2018. How a child rape revealed the problems facing modern India. New report (Web), Kathua, Jammu and Kashmir, India: CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2018/05/17/asia/india-sexual-violence-intl/index.html.

National Informatics Centre, Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology, Government of India. 2017. Beti Bachao Beti Padhao. https://secure.mygov.in/group/beti-bachao-beti-padhao-0/.

Nundy, Karuna. 2018. Twitter Post. May 27, 2018, 3:34 a.m. https://twitter.com/karunanundy/status/1000641271654895616.

Prasanna, Chitra Karunakaran. 2016. “Claiming the public sphere: Menstrual taboos and the rising dissent in India.” Agenda 30 (3): 91-95. doi:10.1080/10130950.2016.1251228.

Safvi, Rana. 2018. Twitter Post. May 28, 2018, 3:26 a.m. https://twitter.com/iamrana/status/1001001875787968512.

Sinha, Disha. 2018. Facebook Post. May 25, 2018, 8:59 a.m.

South East Asia Regional Office for World Health Organization. 2018. Health situation and trend assessment. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/health_situation_trends/data/chi/sex-ratio/en/.

Srivastava, Roli. 2018. “Child brides sold into sex slavery, domestic work, say Indian officials.” Reuters. May 1. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-trafficking-marriage/child-brides-sold-into-sex-slavery-domestic-work-say-indian-officials-idUSKBN1I230N.

The Indian Express. 2018. “‘Beti bachao roti banwao’: Regressive campaign gets massively criticised on Twitter.” The Indian Express. May 28. http://indianexpress.com/article/trending/trending-in-india/beti-bachao-roti-banwao-twitter-reactions-5194514/.

UNICEF. n.d. UNICEF India: Child Marriage. http://unicef.in/Whatwedo/30/Child-Marriage.